All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

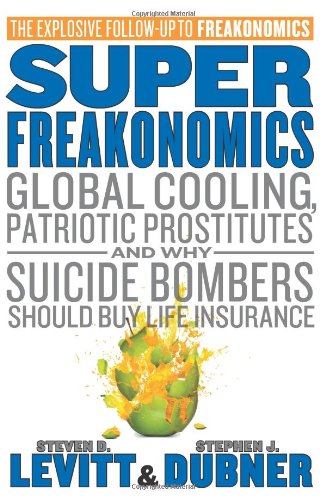

Superfreakonomics by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner

If for some fantastic reason you were to be reduced to the size of a thimble, and the 288 pages of Superfreakonomics were turned into a real life animated story book, it would be interesting to think whether or not you could make it out, without wholeheartedly converting into an economist. Suddenly, a prostitute would walk up to you, but she would only stay for the prime price, because she doesn’t have a pimp. Then a suicide bomber would shake your hand and ask you about your day, then you would find out how giving people truly are (when there is no incentive for them), at which point you would wash your hands, nobody likes a germy doctor. And, as Mount Pinatubo erupts, you shoot out and find yourself closing the last page of an adventure you wish you could ride on again. With so much spastic jumping from subject to subject how could there be any unifying theme? Yet all the wondrous magic that Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner have replicated from Freakonomics(2005) into its reincarnate Superfreakonomics(2009) does have a theme-people and what they will do when incentives are thrown at them.

The chapter setup as in most of the book starts out with a burst of enthusiasm through one question, but to get the answer to the question, you must read the entire chapter. It’s as if the minute you open the book incentive fall into play, the pose a question, but to gain the reward -the answer- you must finish out the entire chapter. But to analyze Superfreakonomics on a chapter-by-chapter basis would be…redundant, because many of the same questions are discussed and some chapters include much heavier subject matter than others. Instead, listed inside of the front cover are a bold list of questions posed throughout the book that almost always include a “universal lesson”. Who knew such brave and incredible new findings could come from New York City?

How is a street prostitute like a department- store Santa? The answer, although it may seem at first glance to be simple, it is nothing of the sort. First, what does a prostitute do? Yes, she sells sex for money, but, besides that, what she is really selling is opportunity. Not the opportunity you’re probably thinking about right now, it’s more than just sexual; at least it is for Allie. Allie the main protagonist throughout chapter one- saw it in a different way, in a (for lack of a better word) Superfreakonomic way. She was able to hold on her regular year-long job, and take up prostitution during the busy season. When she did this, she began playing with incentives, just like the department store Santa. Santa works strange hours, on days that everybody is on vacation, and the job would be temporary, and the perception of who actually takes a job like that, but at the end he gets an unprecedented amount of mula for, a month or two of work, just like Allie.

Why are doctors so bad at washing their hands? Perhaps the appropriate question would be -In a hospital better than many of those surrounding it in the world, how can doctors be allowing so many women and children to die? The technological advances were there to be able to deliver most of the babies safely without fear of injury, and allowing the mothers to live as well, but so many were dying. The fatality, was a special kind of fever that was only present in pregnancy cases, and through the teasing out of experiments, one of the doctors determined that the hospital was what was killing them. The statistics showed that a mother giving birth in a hospital was more likely to die than a mother giving birth on the street. It was a scary notion that the hospitals, doctors were killing people, but it’s even more incredible to find that they were all dying because they aren’t washing their hands! And now to answer the first question, doctors are so bad at washing their hands, and still are, because, they are slightly egotistical, and it would take so much time away from actually treating the patient for what they came in for. A universal theme that should be redundant by now, docs wash your hands.

How much do good car seats do? The answer to this question is quite simple, they perform slightly worse than regular seatbelts. But why do parents, and the government, continue to sensationalize the importance of having a good car seat? Security. When a parent buys a super- duper car seat-which almost always functions the same as a seatbelt- what are they actually buying? Security, and peace of mind, with that extra c-note they are purchasing the false peace of mind that one’s little angel will be protected. In short and for complete clarification of the above question, car seats do a lot of good, if you are an OCD parent, otherwise strap your child of ages three and older up in a seat-belt.

What’s the best way to catch a terrorist? This is probably the most interesting find in the entire book, because unlike the other questions where the means of getting there was the entertainment, because the answer was so short, this answer came rather quickly, and in an algorithm. In the specific example in the United Kingdom, after a July,7,2005 attack, the police force had been attacked by Islamic fundamentalists, the algorithm is as follows. The terrorist(s) would most likely have a Muslim name, and male, between the ages of 26-35. Traits that were tell-tale signs of a terrorist(s) were if they; “own a mobile phone, be a student, rent, rather than own, a home.” So, if one plans on catching a terrorist, these are some things to look out for.

Are people hardwired for altruism of selfishness? This question seemed to come up multiple times in Superfreakonomics. And it is exactly the kind of thing that the dynamic duo feeds off of, that is correcting conventional wisdom. At first through a series of experiments, it seems as though people were hardwired at birth to give through an experiment called the Dictator. In said game, ‘subject A’ would be given twenty dollars and asked whether or not he/she wanted to share the money with ‘subject B’. Overwhelmingly, people were philanthropists! “The only problem was it worked in practice, but did it work in theory?” No, as List, an economist figured out when he altered the experiment to making the subject earn the money before he/she decided whether or not to give it to a stranger. While answering this question, it also made the reader aware that experiments can yield answers that don’t always portray the actual truth. With that fact, Superfreakonomics jumped to the Kitty Genovese case, proving that perhaps the news article that made the case famous was both sensationalized and false. As to the answer of the question, neither.

An appropriate final question would have to do with the “Global Cooling” chapter. How do we prevent global warming? First, the book never actually conflicts as to whether or not global warming is a threat or even true, instead, it assumes that it is true based on statistics, and that there is an obvious dangerous warming of the earth. This is a real human/environment interaction that is impacting our world. But, how do we as a society fix the problem? It’s a cheap and simple fix; pollute the stratosphere with sulfur dioxide! This must be the only straightforward answer Freakonomics has ever given, and it makes total sense, unfortunately we have a society filled with timid people and Al Gores’.

As mentioned above, Superfreakonomics is a spastic tale of human life through the eyes of a rogue economist, and a former New York Times Magazine editor. It is breathtaking, groundbreaking, and is sure to make the reader a true Freakonomist, which is what the authors intended when they wrote the book. I deeply enjoyed this read, I was blown away by it, and can’t help but think like an economist. Alas, I feel like a dumped date on prom night, please write another! Perhaps Extrasuperfreakonomics!

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.